Open main menu

Open main menu

Open main menu

Open main menu

This essay will examine the collection and use of intelligence during Gen. Robert E. Lee's Maryland Campaign from 2 September through 20 September 1862 including Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's efforts concentrating on the period leading up to the Battle at Antietam on 17 September 1862. On that day and after, the armies were in close contact with each other diminishing the need for active intelligence. Areas to be discussed will include cavalry activities, scouting and screening; human intelligence, spies, scouts, prisoners of war, deserters, and local citizens; and newspapers, intercepted correspondence, deception, and signal stations. How information which is collected is then analyzed and acted upon by the two army commanders, Lee and McClellan, will be reviewed. Here the activities of Allan Pinkerton, McClellan's famous intelligence operative will be briefly mentioned. Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown (Jeb) Stuart, Lee's cavalry commander, played a major role during the campaign so his successes and failures will be detailed as will those of his counterpart, McClellan's cavalry leader, Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton.

The Lost Order of which McClellan said "Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home"1 will be discussed in detail to show why this extraordinarily valuable piece of intelligence which could have led to the destruction of the widely separated parts of Lee's divided army did not do so.

Lee's strategic plan was based on his belief that the time was ripe for a move into the border state of Maryland not only to continue the momentum he generated in defeating McClellan during the Seven Days' Campaign and Maj. Gen. John Pope at Second Manassas, but to draw the Union hosts north of the Potomac and away from war-ravaged Virginia. He was certain that the Union army was demoralized after those battles and that the time was propitious to carry the war north before their army could reorganize and reinforce.2 Concomitantly, he thought it reasonable that, also based on his earlier experiences on the Peninsula, any pursuit by Union forces from the defenses around Washington would be slow, cautious, and disorganized. Additionally, after months of hard campaigning, his troops desperately needed time to rest and recuperate so the lush, untouched farms and fields of Western Maryland and possibly even Pennsylvania could provide the victuals and forage his army required.3 Lee also expressed several other reasons for this campaign including luring potential recruits into his army and bringing Maryland whom he perceived as one of the Confederacy's irredenta back into the fold.4 Influencing the 1862 U.S. Congressional elections was a part of his thinking as was the effect a winning military campaign would have on foreign governments' opinions of aid to the South.5 Public opinion in the North as well as in Britain and France was also on Lee's mind. And given northern resistance at the Battle of Chantilly on 1 September 1862 after the Union defeat at Second Bull Run, it was clear to Lee that he would not be able to turn Maj. Gen. John Pope's flank and get closer to the Union capital. Even if he did, Lee knew that the chain of forts protecting the capital would make it impossible to attack them successfully plus investing it was similarly unrealistic.6 Given Lee's views of his previous successes, and the potential for further progress towards freeing the South, Lee had very few viable strategic moves left that would give the many attainable advantages this move into Maryland could provide.

He further believed that another military success against the Union hosts would finally discourage and exhaust the northern populace who had hoped for a quick, decisive victory against the Confederacy. Lee's victories during the Seven Days and Second Bull Run forced Union forces away from the gates of Richmond back to the Union capital's doorstep surprising and shocking Union citizens. He also knew that the large forces his government had gathered allowed him to defend Richmond and would also permit offensive action northward. Another such effort might be difficult to mount so he had to make the most of what he hoped would be the final blow needed to end the war.7 The only question now for Lee was which way to move to entice the enemy to come out of its Washington defenses to confront him before Union reinforcements could be built up which would permit them to attack at their leisure. Since he knew he could not stay where he was in Northern Virginia due to logistics and inability to maneuver, did not wish to retreat towards Richmond, and could not attack Washington, he decided that his best move would be north into Maryland, perhaps even into Pennsylvania.8

McClellan was called on by President Abraham Lincoln to reorganize Pope's defeated army and assemble a viable force to face Lee in Maryland and defend the capital.9 While Lincoln had serious doubts about McClellan's will to fight in the field as did his cabinet, he was the best Lincoln had on hand in this emergency especially as Lincoln knew he was an excellent organizer and administrator. In addition, other generals to whom command of a field army to confront Lee was offered, declined.10 The army McClellan put together consisted of some of Pope's severely beaten units from the Army of Virginia combined with his own troops from the Army of the Potomac from the Peninsula as well as regiments of new units pouring into Washington. These were flooding in responding to Lincoln's call for 300,000 more men in July and then in August for 300,000 more nine month militia. However, McClellan had to be concerned about the combat readiness of the more than 20,000 green troops which made up a large part of his army heading west to face Lee's veteran troops.11 Many units were even added to divisions as the army corps moved out from Washington. McClellan was not taking the weeks Lee assumed he would to form an army for pursuit. Perhaps with Confederates at Washington's doorstep, and with the spotlight on him to protect the capital and northern states, McClellan's normal conservative and studied approach to preparation was put aside in this emergent situation.

His highest priority was to protect Washington. And as rumors poured in, the Union army high command and the Lincoln administration were alarmed and confused by Lee's movement north. It was feared that Lee might surround and attack the capitol and then move on Baltimore. Alternatively, it was thought he could continue north from his crossing point near Leesburg, Virginia, some thirty miles up the Potomac River, and move into Pennsylvania. There, he could attack railroad links to the west and then its capital, Harrisburg, possibly then moving on Philadelphia or even New York City. Given these uncertainties, McClellan had to maintain his corps on a 10-mile wide arc--later extended to 16 miles--until Lee's intent was divined.12 He also had to leave a large force in the Washington defenses in the event that Lee's move north of the Potomac was a feint as Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck feared to cover an attack south of the Potomac River towards the capital.13 Therefore, he initially moved cautiously organizing his units on the move as he probed west and northwest. Certainly the new units under green officers were unused to marching and military discipline slowing down their columns' progress. Some had received their marching orders even before they were issued muskets. Straggling was a serious problem for McClellan as well as Lee, perhaps even more so.14 And later during the battle of Antietam on 17 September, many of these untested regiments panicked under fire which resulted in one instance with the entire Union attack breaking down.15

But McClellan likely felt better as Union forces occupied Frederick on 12 September since he knew then that Lee could not easily attack Washington or Baltimore because it would have his Army of the Potomac on its flank in both cases. So even though he was unaware of the disposition of Lee's forces, his army moved with more speed as it probed for Lee's units.16 The stage was set for McClellan's serendipitous finding of the Lost Order the next day, 13 September.

Lee, like McClellan, was his own "chief of intelligence" and never had a staff officer assigned specifically to intelligence work.17 As Lee developed his headquarters staff, it is likely that one or more helped Lee with intelligence-related matters but there is no evidence that any one of Lee's staff was assigned intelligence duties.18 But while he sometimes may have lagged behind his opponents in collecting or analyzing information, he excelled at the most difficult component of the intelligence process, applying it.19 McClellan had Pinkerton but he served only as another source of written reports for McClellan, not as McClellan's intelligence analyst.20 Stuart came closest to being Lee's intelligence chief as he was the one who brought more information to Lee than anyone else. Lee affirmed this when he was notified of Stuart's death at Yellow Tavern: "He never brought me a piece of false information."21 One of Stuart's couriers, Lt. John Mosby, had not yet reached prominence as a scout or partisan leader and played only a minor role during the Maryland Campaign most notably aiding a wounded Union officer who turned out to be one Isaac J. Wistar who thanked Mosby in his memoir.22 Regardless, Lee recognized the value of scouts and urged their use.23

Confederate spies in and around Washington supplied some information to the Confederates. One, Capt. Thomas N. Conrad, a chaplain of the 3rd Virginia Cavalry, operated a spy net, but was only able to get information to Richmond and not directly to Stuart or Lee due to heavy Union troop movements in Northern Virginia. But one of Conrad's spy networks may have aided Lee by passing on information regarding McClellan's troop strength. A Confederate spy, Charles T. Cockey, operated a way station on the Confederate Secret Line at Reisterstown, Maryland, northwest of Baltimore. Cockey said that he went to Frederick, Maryland, and reported this information directly to Lee.24 Another spy who worked closely with Stuart, Frank Stringfellow of the 4th Virginia Cavalry, and was of great help during the Battle of Second Bull Run, may have spied on Union activities closer to Union lines but there are no reports available of his activities.25 Stuart's cavalry was successful at screening near Leesburg on 4 September keeping Union cavalry away and driving an independent company of cavalry from the town towards Waterford. Their demonstrations at Alexandria and Groveton however, did not fool Pleasonton or Halleck who believed that this show of force was to cover a crossing of the Upper Potomac. 26

North of the Potomac, Lee had to rely heavily on Stuart, his "eyes and ears," for intelligence of McClellan's movements. But Stuart, like Lee, was probably lulled into a sense of complacency as the army bivouacked around Frederick on 7 September.27 After all, based on what they knew of McClellan and his snail-like crawl up the Peninsula just a few months ago, it would likely take weeks for him to reorganize the defeated and demoralized army around Washington. Then, many more days would pass before he would leave the Washington defenses adopting his usual plodding pace. In the meantime, Lee and his army could rest and feast on the bounty of Maryland's late summer harvest after months of difficult campaigning. Once McClellan did make an appearance, Lee's army would have regained its strength, gathered up its stragglers, and then be able to maneuver perhaps north to draw McClellan further away from his base and attenuate his line of operation.

But these lazy, late summer days may have lulled Stuart into more complacency than they should have done. Stuart, as the cavalry division commander reporting directly to Lee, could not help but be influenced by the relaxed control of his army commander, but the danger was that the "Gay Cavalier" needed tighter control and guidance than any of Lee's other commanders. Stuart was an excellent cavalry leader and personally brave, but he was also prone to showy, flamboyant, and sometimes impulsive behavior, seeking and enjoying public acclaim and female adoration.28 Unfortunately during the beginning of this campaign, Stuart was true to form with his penchant for frolic and female attention. One of his escapades occurred on the evening of 8 September near his headquarters at Urbana, Maryland, the center of his cavalry screening line. Stuart and his Prussian aide, Maj. Heros von Borcke, planned a ball at an abandoned female academy."29 Stuart supplied music using Brig. Gen. William Barksdale's 18th Mississippi band and decorated the hall with their Mississippi regiments' battle flags while von Borcke supplied the hand-written invitations and supervised the decorations adding bouquets of roses.30 While the ball progressed splendidly, about four miles away to the southeast towards Hyattstown, the 1st New York Cavalry decided on a reconnaissance. News of this skirmish was brought to Stuart at the ball; Stuart and his staff mounted and rode to the scene finding that the 1st North Carolina Cavalry had already driven off the pesky New Yorkers. They returned to the ball and recommenced the festivities only to be again interrupted this time by Confederate casualties being taken upstairs above the ballroom; many of their ladies help treat the wounded. The ball then continued to dawn.31 Stuart and his staff spent the following day in needful relaxation.

While Stuart's actions in camp in Maryland were similar to those in his Virginia headquarters, he showed questionable judgment by continuing to pursue such merriment in unfriendly country in the face of the Army of the Potomac advancing towards him. One of his headquarters staff called the sojourn at Urbana "delightful" since "[t]here was nothing to do but await the advance of the great army preparing around Washington" and enjoy "the society of the charming girls around us to the utmost."32 Clearly, Stuart's mood of jollity and lack of serious concern about the enemy prevailed and worse, infected his staff. But complacency in the Confederate camps should not have infected Stuart since he, as Lee's eyes and ears, should have watched the enemy closely to ensure that Lee was not surprised. Waiting the advance of the great army was exactly what he should not have been doing, rather, he should have been aggressively scouting for any sign of that advance. His poor supervision of his scouting efforts was his most noteworthy failure in this campaign.

Lee's army was in a generally unfriendly part of the state so the numbers of friendly civilians available for questioning were reduced. And Lee feared that here in Maryland, as in Virginia, "The country is full of spies and our plans are immediately carried to the enemy."33 Initially, there were few prisoners or refugees to interrogate. Thus Stuart's reconnaissance duties were critical during this time. Lee's other sources such as newspapers were not as plentiful since he lost those which might have been delivered to him through the Confederate Secret Line were he in Virginia.34 Lee was well aware of the use of newspapers as intelligence sources as well as opportunities for spreading disinformation: "I am particularly anxious that our newspapers may not give the enemy notice of our intentions" while "an enigmatical paragraph in the Dispatch [about D.H. Hill's movements]...may be advisable."35 And as will be noted below, he missed the newspaper containing a story of the finding of his Special Order 191 (S.O. 191), which would become known as the famous Lost Order. But he did find some newspapers to read such as the Baltimore Sun but there is no record of much useful operational information gained from them.36 However, since intelligence in a mostly hostile area was not as readily obtained or as reliable as in Virginia, Lee was forced to use what was at hand.

There is little documentary evidence of Lee's intelligence sources save for the capture by Stuart's troopers of the Union lookout station on Sugarloaf Mountain on 6 September. Although they held it until Pleasonton's troopers recaptured it on 11 September, nothing is reported of what use they made of its commanding vista although the Confederates did establish a signal station there.37 Similarly, while the Confederates cut telegraph wires, interrupted train service and breached the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal, no evidence is found showing that any telegraph messages or Union correspondence were intercepted in Maryland. And no successful use is documented of a Confederate "secret service fund of several hundred dollars in greenbacks... [available] through Col. Porter Alexander."38

Lee, on the evening of 4 September before crossing the Potomac, did take advantage of talking for several hours with Bradley Tyler Johnson. A former Marylander, he had led a Maryland regiment for the Confederacy. Johnson, a well-educated lawyer, likely gave Lee details of the "'topography, resources and political condition'" Lee would encounter. Apparently, he gave Lee a somewhat pessimistic view of the welcome Lee's army would receive but Lee was most interested in the topography of the area to help him decide the best place to cross the Potomac. As usual, the Confederate commander was more interested in the practical aspects of the campaign although not neglecting political ramifications.39

Stuart's inability to accurately gauge Union movements and numbers may not necessarily reflect poorly on Stuart's scouting efforts but show the effectiveness of Union efforts to thwart such attempts.40 Also, operating in a hostile country in the face of large Union forces had to negatively affect Stuart's reconnaissance even though his cavalry division was approximately equal in size to Pleasonton's division.41 Stuart's tardy official report dated 13 February 1864 about his Maryland Campaign typically underplays his inability to accurately understand Union deployments and movements. For example, he reported that on 12 September "The enemy studiously avoided displaying any force, except a part of Burnside's corps, and built no camp-fires in their halt at Frederick that night" so Stuart, despite taking "[e]very means...to ascertain what the nature of the enemy's movement was", was unsuccessful.42 The normally resourceful Stuart was here stymied by lack of campfires and was unable to use any of his ingenious schemes to surmount Union screening efforts. In a statement in a dispatch to Stuart on 12 September Lee perhaps shows his concern with Stuart's performance when he told him to "Keep me advised of the movements of the enemy, and do not let him discover, if possible, our movements." It is remarkable that the army commander in the middle of a campaign had to remind his cavalry commander of the two most important missions of the cavalry: reconnaissance and screening.43 It may have been that Lee had only been in command of the army a very few months and was still learning the abilities and limits of his generals, or perhaps due to the lack of good intelligence from Stuart, he was concerned about his cavalry's performance.

Stuart, in a poor tactical move, sent off about a third of his cavalry on a fruitless mission to the north. Fitz Lee and his brigade was ordered to learn of Union movements on 12 September but after terrorizing the town of Westminster and destroying a B&O Railroad bridge, nothing was heard from him again until he returned to Boonsboro late on the 14th. With the effective Union cavalry screen, Stuart's troopers could tell him little of McClellan's more rapid movements northwest: "The eyes and ears of the Confederate army, while neither blind nor deaf, saw and heard very little on September 12."44

One aspect that did work well for the Confederates was their spreading of disinformation. These successes are revealed by the many reports received by Washington and at McClellan's headquarters showing Lee heading for Washington, Baltimore, Harrisburg or Philadelphia. The result was that Lincoln, Halleck and McClellan had to ensure that these potential targets were covered. McClellan did so by using his army to cover both Washington and Baltimore while keeping an eye on movement north towards Harrisburg and Philadelphia. Confederate cavalry, likely encouraged by Stuart, was not averse at planting misleading information and perhaps excelled; in a series of reports by Pleasonton on 7 September, Baltimore was listed as the object of the Confederate movement based on information he received from civilians. In one report, the Confederate troopers told a group of female admirers they were going to Frederick and then to Baltimore.45 But "Stonewall" Jackson provided the best example as he prepared to leave Frederick on 10 September. As he entered the town, he pulled off to the side of the road and in "an uncharacteristically loud and ostentatious scene...He demanded from his engineer a map of Chambersburg and vicinity, and then made inquiries of the citizens standing about regarding the various roads leading to Pennsylvania."46 But as Dr. Joseph L. Harsh, the noted Antietam scholar, points out, had Jackson known that Lee would later that day divide the fourth part of his army and send it to Hagerstown towards Chambersburg, Jackson may have tried a somewhat different ruse. Lee's comments about Stuart also shed light on the disinformation campaign: "Stuart with his cavalry was close up to the enemy and doing everything possible to keep him in ignorance and to deceive him by false reports, which he industriously circulated."47 But the Union rumor mills were already working full time even without help from the Confederates. Reports were coming in from all points of the compass, most of them false or at least exaggerated. One even had Braxton Bragg coming down the Shenandoah Valley with 40,000 troops.48 Until physical contact was made with Lee's army, McClellan had to deal with the Confederates effective disinformation and the myriad reports he received, both accurate and wildly incorrect, coming in from many sources.

Lee's abilities to participate in some of the activities which might have helped him understand what McClellan was up to were hampered by injury. He had incurred a sprained and a broken wrist on 31 August in a fall which limited his mobility and therefore his ability to command the army especially during the battle at Antietam. He rode in an ambulance from that time to 16 September when he was able to mount his horse and be led by an aide.49 It took some six weeks before Lee could even sign his name.50 His disability could not have come at a worse time as he needed all his physical abilities in his fight for his army's life during this campaign.

Because of the poor scouting by Stuart and the dearth of other helpful sources of information, Lee suffered from both lack of quantity and quality of information. Combined with Stuart's lackluster reconnaissance, Union cavalry was effective in screening Stuart's troopers thus Lee was surprised at the heavy attacks at Turner's, Fox's and Crampton's Gaps on 14 September. The Union attack at Turner's and Fox's Gaps came close to destroying that part of Lee's army which was fighting to ensure that McClellan could not turn south and fall with his full strength on McLaw's rear at Harpers Ferry. Lee's drawing out the Union army from its Washington defenses almost resulted in Lee's destruction as he was unable to gauge the strength and alacrity of its movement and therefore unwisely divided his army into four then five parts. But McClellan's intelligence efforts had an unexpected success at Lee's expense due to the finding of the Lee's S.O. 191.

McClellan's intelligence in this generally friendly country was little better than Lee's but for different reasons: Lee suffered from a paucity of good information while McClellan had too much information with no effective way to collate and analyze it. Stuart and Pleasonton maintained fairly effective cavalry screens thwarting both Union and Confederate efforts to gauge the other's movements.51 That Stuart's screening and patrolling were effective is shown by the fact that none of the several messengers sent to Harpers Ferry by Halleck or McClellan made it through to their destination. At least Lee was not hampered by greatly exaggerated reports of his opponent's troop strengths to the same extent as was McClellan who had Allan Pinkerton's help. But Pinkerton contributed little to Union efforts during the Maryland Campaign as his staff size compared with what he had on the Peninsula with McClellan was cut in half: he was operating with seven agents in Maryland but it included one of his best, John Babcock. Pinkerton's staff in Washington was also reduced. And again, as during the Peninsular Campaign, Pinkerton did not send out scouts or engage in espionage but rather relied on interrogation of deserters, stragglers, and prisoners much to the dismay of Babcock.52 However, there is evidence that Pinkerton paid for information from local citizens while some were enlisted as guides. A tax collector for the Poolesville district on 6 September brought information to Pleasonton and was put on Pinkerton's payroll as were nine others added later.53 Evidence of the use of Union spies is sparse but there is a statement that "'a spy acting as a Confederate courier was discovered near Harpers Ferry and was at once hung to a limb of a tree on the road-side.'"54 If there was one intelligence coup of this campaign, it was McClellan's finding Lee's S.O. 191 on 13 September. After finding this order and adding it to the information he already had, McClellan arguably had all the information he needed to annihilate Lee. However, he was unable to discern which was accurate and reliable, and he characteristically failed to move quickly enough even after finding the Lost Order.55 Following his usual practice, McClellan served as his own chief of intelligence so had to review all the reports that Pinkerton generated as well as the many telegrams and other reports sent to his headquarters. This large paperwork burden likely contributed to McClellan's difficulty in analyzing the plethora of documents and data he received.56

McClellan's overestimates of Lee's available forces began even before Lee ventured north of the Potomac River. On 28 August 1862 McClellan informed Halleck that "Reports numerous, from various sources, that Lee and Stuart, with large forces, are at Manassas; that the enemy, with 120,000 men, intend advancing on the forts near Arlington and Chain Bridge, with a view to attacking Washington and Baltimore."57 McClellan's estimates of Lee's army during the campaign were based on wildly varying reports from civilian and official sources but there is no evidence that McClellan saw any of the more realistic figures available. In a report to Lincoln on 10 September, he said that "statements I get regarding the enemy's forces that have crossed to this side range from 80,000 to 150,000."58 He seems to have settled on the estimate of 120,000 as realistic based on the reports he saw. But it is also likely that had he seen lower estimates he would have ignored them as they did not fit in with his thinking.59 It is surprising that he did not adopt Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin's estimate of 200,000 reported from a clergyman conversing with Confederate troops before they left Frederick on 10 September.60 Pleasonton, too, was limited to questioning civilians who may have picked up information from the Confederates passing by and from deserters and prisoners gathered in or captured by the efforts of his five brigades. Stuart's cavalry screen was very effective remaining virtually unbroken for most of the campaign thus depriving Pleasonton and McClellan with first-hand knowledge of Lee's movements.61

Cutting telegraph lines was one favorite Confederate tactic and this high priority mission was always on the agenda of cavalry as it normally led the infantry. Confederate troopers actively pursued this mission on their advance into Maryland as virtually all lines were cut in their areas of operations.62 The telegraph line and the B&O Railroad were cut on 6 September isolating Harpers Ferry; the telegraph line was even cut beyond Harpers Ferry by 2 September.63 But given the number of telegrams sent among Union military and civilian officials in Washington, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, rerouting on remaining lines except for Harpers Ferry was sufficient. Certainly the early loss of the lines to Harpers Ferry, although predictable, helped doom that garrison. There is no record of any intercepts or false information sent by telegraph but some of the best information that was obtained and transmitted for either side was done for the Union by William B. Wilson.

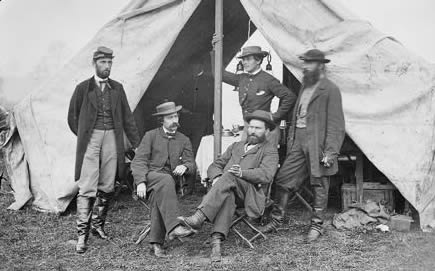

The services of Wilson were indirectly provided courtesy of Governor Curtin. As rumors had Lee heading for Pennsylvania, its citizens were frantic and Curtin was desperately concerned trying to obtain Federal troops as well as better information on Lee's movements. He tried to get Lincoln to send 80,000 troops and equipment to Pennsylvania while calling up the state's militia but instead, Lincoln sent Maj. Gen. Andrew Porter to muster in and organize volunteers and Brig. Gen. John F. Reynolds to lead the state militia. Curtin, at McClellan's urging, had set up an intelligence group led by cavalry Capt. William J. Palmer. Palmer, a very competent officer, with help from Wilson, was able to use his few troopers as scouts to keep track of Confederate movements as well as interrogate refugees and deserters. Wilson's abilities to tap into telegraph wires enabled very accurate, prompt reports to be sent to Curtin.64 Unfortunately, Palmer's and Wilson's generally effective and correct reporting was partially negated by Curtin's editing before relaying the information to Washington and McClellan. As amateurs, Curtin and his assistant, Alexander McClure, did not recognize the value of the intelligence they received from Palmer and Wilson so their condensations and interpretations distorted or left out important details. Thus the best field intelligence organization formed up to this time for the Union was ineffectively used materially contributing to McClellan's failure to destroy Lee.65

Palmer's group also inadvertently benefited McClellan at South Mountain. Some of Palmer's men were moving toward Hagerstown from Pennsylvania and reports reached Lee of this Union advance. Lee had to defend against this "threat" not allowing Union forces to menace the army's trains near Hagerstown. Lee divided the fourth part of his army under Maj. Gen. James Longstreet in two, sending Longstreet to Hagerstown to deal with this Union advance coming down from Pennsylvania while Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill stayed at Boonsboro near Turner's Gap in South Mountain. Thus the unintentional scare Palmer's men provided meant that McClellan's attack at Turner's Gap encountered a much smaller force as most of Longstreet's forces were near Hagerstown and had difficulty returning to Turner's Gap when Union forces attacked.

In addition to the personal observations Palmer and his men reported, visual observations from high vantage points were also important. Balloons were not available as Professor Thaddeus Lowe remained near Washington because he had no transportation to help move his cumbersome equipment to try to keep up with the army.66 Fortunately, Sugarloaf (or Sugar Loaf) Mountain, near Barnesville, Maryland, south of Frederick, was an excellent vantage point. It was possible to see Washington some 30 miles to the southeast on a clear day and far up the Potomac River to the Catoctin Mountains to the west.67 It is almost 800 feet higher than surrounding terrain and was part of a Union signal flag relay chain in use from early in the war which proved to be helpful to McClellan's advance. The Union Signal Corps occupied Sugarloaf on 3 September and transmitted by flag information to Poolesville to be telegraphed to Washington. It was in active use spotting Confederate activity on 4 September and reporting a suspected crossing into Maryland near the Monocacy River.68 The signalmen on the mountain, Lt. Brinkerhoff N. Miner and his flagman, A.H. Cook, abandoned their post on 6 September after it was surrounded by Confederate cavalry. During their exodus, they captured a courier with letters from President Davis to Lee but Miner and Cook were then captured by Stuart's troopers. McClellan may have recognized the heights value as he directed Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin to take the mountain quickly: "the earlier we gain the Sugar Loaf the better."69 Taking Sugarloaf was also ordered because it was an "important object" and it "must be carried."70 Although Confederates held it until Pleasonton's troopers recaptured the mountain on 11 September, it was in full operation quickly late in the afternoon of 11 September communicating with Poolesville and the next day a station was reopened at Point of Rocks.71 McClellan noted its use as it reported Union troops moving into Frederick on 12 September.72 While Confederate troops held the mountain for almost six days likely taking advantage of its perspective, there are no records showing the extent of that use other than that it was used as a Confederate signal station.73 The early loss of this post was a serious blow to the Union intelligence gathering effort during the critical early days of the campaign.

Other Union posts of observation were established as the army advanced. One established at Washington's Monument on South Mountain north of the National Road observed the Confederates retreating towards Sharpsburg as well as seeing some of the battle lines forming near Antietam Creek. On 16 September, signal stations or stations of observation were established in preparation for the anticipated 17 September battle: one on the crest of Elk Mountain, one on Burnside's left, one on the right with Meade, and one on the field near McClellan's headquarters. The one located on Elk Mountain "commanded Sharpsburg and Shepherdstown, and also many points of the battlefield, with its approaches. A careful telescopic survey of all points deemed necessary was made, and a full report of the enemy then in from to Sharpsburg, and of the movement visible, sent to the general-in-chief."74

While McClellan and his forces were operating in a relatively friendly area, the information he received was so plentiful and variegated that its analysis was difficult. Since Pleasonton's scouting efforts were nullified by Stuart's excellent screening, McClellan had to rely on other sources for information.75 Unfortunately, many of those sources, while well meaning, were unhelpful, even those from officials such as Halleck and Curtin who sometimes repeated unsubstantiated rumors.76 Once McClellan had Lee's Lost Order in his hands, he had an opportunity to crush Lee but could not do so since he believed Lee outnumbered him and in any event, the relatively slow moving Army of the Potomac with its large percentage of green troops did not have the legs to catch Lee.

On the afternoon of 9 September, after meeting with Longstreet and Jackson, Lee had his chief of staff, Col. Robert H. Chilton, write seven copies on single sheets written front and back of the order detailing the division of his army into four parts.77 (See Appendix.) Jackson later made a handwritten copy for division commander Maj. Gen. Daniel H. Hill, his brother-in-law, assuming that Hill was still under his command. This copy was delivered to Maj. James W. Ratchford on Hill's staff by Maj. Henry Kyd Douglas, one of Jackson's staff. Chilton's copy for Hill was sent by courier and apparently lost; Chilton, in violation of normal headquarters' procedure, never questioned the missing receipt from Hill. It is likely that given the turmoil of getting ready for the move from Frederick, the paperwork niceties were forgotten. Too, the headquarters of the generals were relatively close so the chances of capture of the couriers were slim. The various possibilities of which officer lost the order or how it was otherwise misplaced have demonstrated that it was most probably lost not by Hill or his staff but by the courier carrying the order from Chilton.78 Both copies of the original order for Hill omitted paragraph I dealing with Confederate visitation to Frederick and paragraph II pertaining to one of Lee's staff, Maj. Walter Taylor's, visit to Winchester; neither concerned Hill as a division commander.

The Lost Order was about to meet avid Union readers as the XII Corps advanced to Frederick on Saturday 13 September. The 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment, known as "The Giants," was in the van.79 The regiment camped outside Frederick in a clover field alongside the road near Myers Farm where Corp. Barton W. Mitchell from Company F saw something unusual near the fence bordering the road. It was a bulky package lying in the grass which he picked up and read while a Pvt. John Campbell looked over his shoulder. Mitchell took it to his First Sergeant, John M. Bloss, and they both went to their company commander, Capt. Peter Kopp, and finally to the regiment's commander, Col. Silas Colgrove. Colgrove went immediately to the XII Corps commander, Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams. Williams and his aide, Lt. Samuel E. Pittman examined the paper and Pittman said he recognized Chilton's signature having seen it in the old army.80 The paper was immediately sent to McClellan's headquarters. McClellan wired Lincoln at about noon on the 13th: "I think Lee has made a gross mistake and that he will be severely punished for it....I hope for a great success if the plans of the Rebels remain unchanged....I have all the plans of the Rebels and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency."81

What McClellan had was Lee's plan for his army to cope with the large Union garrisons not abandoning Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry as they should have once they knew that a Confederate army was between them and Washington.82 Since Lee planned to use the Shenandoah Valley as his line of communication, it was critical that these two garrisons not impede this line. Even though Lee initially expected to meet most of his food and forage needs in Maryland, ammunition was critical; Winchester was to be his major supply depot but Lee did not ensure early in his campaign that Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry were evacuated. He fell into the trap of assuming that those garrisons would follow reasonable military tactics but he did not know that Halleck and the veteran department commander Maj.Gen. John Wool had ordered the Harpers Ferry garrison, to which the Martinsburg garrison eventually retreated, to remain in place and to fight until relieved by the Army of the Potomac.83 Thus, Lee divided his army into four parts, three to capture Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry, while the fourth marched to Hagerstown to be ready to continue his Maryland adventure once Jackson had gobbled up the recalcitrant Union garrisons.

Harsh believes that the finding of the order had little consequence because McClellan was already moving more rapidly than Lee believed and that regardless, the Army of the Potomac realistically did not have the abilities needed to chase down Lee's fragmented army.84 Lee reportedly said Stuart informed him on the evening of 13 September that McClellan had been given a document which appeared to be one of some import. But some historians believe that Lee's subsequent actions demonstrate that he did not know about McClellan's finding of the order until March 1863. Then, he read about it in newspapers which reported McClellan's testimony before the congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War.85 After the war Lee declared that McClellan's finding of the order was "a great misfortune" and that up to that time, McClellan had been moving slowly.86 Even though a story appeared in the New York Herald newspaper on 15 September probably written due to the loose talk of some Union officers who learned about the order and told it to the paper's Washington correspondent, neither Lee nor anyone else reading northern newspapers for information during the campaign saw the article87.

Certainly McClellan's responses upon finding the Lost Order and Lee's actions after its finding define the remainder of the campaign, the only controversial aspect being how much difference it made in reality. Many historians agree with Lee's post-war statement that it was the deciding factor; however, some disagree arguing that McClellan was already moving relatively quickly before finding the order and that the order did not give McClellan a realistic chance to destroy Lee unless Lee committed serious blunders. Edwin C.Fishel, who analyzed Union intelligence during the Civil War, holds that had it not been found, McClellan would not have fared as well as he did in Maryland. Because Lee would not have been pressed so hard and so soon, he could have reassembled his army at leisure continuing to draw McClellan further away from his base and attenuating his line of operation.88

But this order was not the talisman which would have helped McClellan destroy Lee's army quickly and decisively: first, McClellan could not be certain it was not a clever Confederate ruse; second, it was already three days old and McClellan had no assurance that it was still being followed as written; third, it contained no information showing Lee's strength; and fourth, the order was somewhat ambiguous. McClellan quickly decided that the order was not a ruse given the circumstances of its finding and the asseveration of Gen. Williams that it was genuine. McClellan was honestly happy to receive this document as it lifted the veil of mystery surrounding Lee's movesóhe was not maneuvering to assault Washington or Baltimore but merely to take the Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg garrisons and head northwest to Hagerstown. In fact, McClellan rejected all information showing that the Confederates were deviating from the plan right up to the day before the battle at Antietam when he saw Lee making a stand there that was not shown in the order.89 That it contained no information about Lee's strength meant that McClellan could continue believing that Lee's forces totaled some 120,000. He saw nothing in the order showing the sizes of the "commands" Longstreet, Jackson, McLaws and Walker led, and the "main body" appellation given to Longstreet's command could easily imply that it was larger than those on the Harpers Ferry-Martinsburg mission. McClellan estimated that this main body had some 50,000 to 60,000 men with 40,000 to 50,000 on the detached missions. Clearly, he felt he had to proceed cautiously in the face of these numbers and that he had to be aware of the threats to his right flank should he move his army to relieve Harpers Ferry. In addition, should he attack Longstreet's main body on the west side of South Mountain towards Hagerstown, he would then have Jackson and McLaws potentially on his rear or left flank. He resolved this dilemma by attacking through gaps in South Mountain using Franklin to take Crampton's Gap, furthest to the south threatening McLaws and relieving Harpers Ferry, and the rest of the army to take Turner's and Fox's Gaps to the north, destroying Longstreet's main body then proceeding south to Harpers Ferry. McClellan's plan was good given the information he had.90

Stuart's inability to give Lee accurate information of Federal movements before the order was found resulted in Lee not worrying about dividing his army into four parts to take Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg. Once it was found, Stuart's inaccurate reports of the ensuing Union pursuit put Lee's divided army at risk of being defeated in detail because Stuart, and therefore Lee, believed that McClellan was marching the bulk of his forces directly to relieve Harpers Ferry. That this made good military sense for McClellan in Lee's eyes cannot be disputed. But both Lee and Stuart overestimated the numbers of Union forces sent directly to rescue the Harpers Ferry garrison, and he did not know, because of lack of good intelligence, that the heaviest Union forces were instead being sent to Turner's Gap. McClellan believed that he could send his forces through the gaps in South Mountain then turn south to relieve Harpers Ferry. His plan was only thwarted by that garrison's precipitate surrender. Another major factor contributing to Lee's near disaster at South Mountain was Stuart's and Lee's lack of knowledge that Jackson had not quickly taken the Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry garrisons according to plan. Once Lee learned of this delay, he quickly realized that he had to prevent McLaws from being overwhelmed from the rear so Lee now had to defend the South Mountain gaps. Added concern for Lee was that his army was then fragmented into five parts since he had sent Longstreet with the army trains to Hagerstown based on an inaccurate report of a Union advance from Pennsylvania. Here again, accurate reports would have allowed Longstreet's forces to remain closer to Boonsborough to have given quicker support to Hill at the South Mountain passes. One could easily argue that Stuart should have been charged with helping to ensure that Lee's scattered units would remain in better contact with the army commander but evidence shows that Lee's three forces contending at Harpers Ferry and even Stuart himself maintained inadequate and tardy contact with army headquarters. Poor contact among his widely spread forces contributed to Lee's problems coordinating his army; poor communication occurred despite having cavalry detachments assigned to the detached commands.91 McClellan's heavy attacks on Turner's, Fox's and Crampton's Gaps surprised Lee and Stuart as they expected McClellan would quickly move east of South Mountain directly from Frederick to relieve Harpers Ferry.

During the Maryland Campaign, McClellan, in finding the Lost Order, had in his hands one of the most important intelligence discoveries in the history of U.S. military operations. He used it to deal Lee a strategic defeat at the Battle of Antietam and permit Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation but he did not crush Lee's army. McClellan's failure to decimate Lee has been defended by some historians and criticized by others while, on the other hand, most of Lee's actions have been praised.92 Even though McClellan had sufficient correct information to deal Lee a severe blow while the Confederate army was split into four, then five parts, he did not move swiftly enough to accomplish that destruction. One of the main reasons for his cautious movements was his belief that he was heavily outnumbered. Since the information he saw and had reported to him contained wildly varying estimates of Lee's strength, he had little reason to suspect that his forces were much stronger than his opponents'. In addition, his active scouting efforts using Pleasonton's cavalry were frustrated due to Stuart's excellent screening. While he had a plethora of information from many human sources such as prisoners of war, civilians, scouts, etc., their information was so varied that it was unhelpful. Since he served as his own chief of intelligence, he did not have the time to effectively sort out and analyze the flood of information received at his headquarters thus once he had the Lost Order in his hands, he slavishly followed it, in fact more closely than did Lee and his generals. Clearly, he would have done much worse against Lee without this find, but he should have accomplished much more.

Lee, on the other hand, showed what audacity and hard marching and fighting could accomplish even when the enemy knows the disposition of one's army. Lee was fortunate to have Stuart provide excellent screening for his army but failed to ensure that Stuart's scouting was as active as it should have been in unfriendly country. Lee and his generals were clearly lulled into believing that the Union army having been recently defeated on the Peninsula and at Second Bull Run was demoralized and shattered needing weeks to restore its fighting ability. Additionally, once McClellan took command, Lee was certain that McClellan would take additional weeks to begin the chase. Based on Lee's experience on the Peninsula, that was a reasonable view but Lee's assumptions failed. Not only did McClellan advance relatively rapidly forming his new army on the move, but he then found Lee's operational plan. When added to these unexpected events, the failure of the garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry to follow normal military procedures and withdraw once their lines of communication were severed concerned Lee as they then impeded his line. While Lee was still relatively new to command of this army, he may be faulted for having an inadequate headquarters staff having no one assigned any intelligence duties other than Stuart and perhaps operating too casually as shown when the missing receipt for a copy of S.O. 191 was not questioned. McClellan's finding of the order combined with Lee's ambitious timetable in the order and Jackson's casual marches to Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry meant that McClellan had even more opportunities to destroy Lee in detail. Only through luck, hard fighting, and excellent leadership by Lee and his commanders at South Mountain and Antietam did he salvage his army and fight McClellan to a tactical draw at Sharpsburg.

While Stuart's scouting did not serve Lee well during the campaign, his screening effectively limited Pleasonton's scouting for McClellan thus stultifying this important part of Union information gathering. Passive intelligence sources worked better for McClellan but given the large number of reports, many contradicting, McClellan disregarded many which were accurate in favor of those which fitted with his view. Confederate disinformation added to the poor quality of many of these reports while Union efforts in using disinformation were nil. Reports which were accurate such as those from Capt. William J. Palmer were lost in the midst of the flood of information McClellan had to digest. Newspapers and captured correspondence played no important role as sources of information and there were no reported instances of intercepted signal or telegraph communications. Thus cavalry reconnaissance and screening served both sides best although Stuart's troopers bested Pleasonton's in scouting. Active scouting best exemplified by Palmer's activities only marginally helped McClellan since Palmer's reports were poorly summarized by Curtin before being sent to McClellan. The most egregious failure of the campaign for Lee was the loss of S.O. 191 while for McClellan it was his inability to make better use of its discovery.

-- Laurence Freiheit, Berkeley Springs, West Virginia

AotW Member

© 2008, Larry Freiheit

Special Orders 191*

SPECIAL ORDERS No. 191.

HDQRS. ARMY OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA,

September 9, 1862.

I. The citizens of Fredericktown being unwilling, while overrun by members of his army, to open their stores, in order to give them confidence, and to secure to officers and men purchasing supplies for benefit of this command, all officers and men of this army are strictly prohibited from visiting Fredericktown except on business, in which case they will bear evidence of this in writing from division commanders. The provost-marshal in Fredericktown will see that his guard rigidly enforces this order.

II. Major Taylor will proceed to Leesburg, Va., and arrange for transportation of the sick and those unable to walk to Winchester, securing the transportation of the country for this purpose. The route between this and Culpeper Court-House east of the mountains being unsafe will no longer be traveled. Those on the way to this army already across the river will move up promptly; all others will proceed to Winchester collectively and under command of officers, at which point, being the general depot of this army, its movements will be known and instructions given by commanding officer regulating further movements.

III. The army will resume its march tomorrow, taking the Hagerstown road. General Jackson's command will form the advance, and, after passing Middletown, with such portion as he may select, take the route toward Sharpsburg, cross the Potomac at the most convenient point, and by Friday morning take possession of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, capture such of them as may be at Martinsburg, and intercept such as may attempt to escape from Harper's Ferry.

IV. General Longstreet's command will pursue the main road as far as Boonsborough, where it will halt, with reserve, supply, and baggage trains of the army.

V. General McLaws, with his own division and that of General R. H. Anderson, will follow General Longstreet. On reaching Middletown will take the route to Harper's Ferry, and by Friday morning possess himself of the Maryland Heights and endeavor to capture the enemy at Harper's Ferry and vicinity.

VI. General Walker, with his division, after accomplishing the object in which he is now engaged, will cross the Potomac at Cheek's Ford, ascend its right bank to Lovettsville, take possession of Loudoun Heights, if practicable, by Friday morning, Keys' Ford on his left, and the road between the end of the mountain and the Potomac on his right. He will, as far as practicable, co-operate with Generals McLaws and Jackson, and intercept retreat of the enemy.

VII. General D. H. Hill's division will form the rear guard of the army, pursuing the road taken by the main body. The reserve artillery, ordnance, and supply trains, &c., will precede General Hill.

VIII. General Stuart will detach a squadron of cavalry to accompany the commands of Generals Longstreet, Jackson, and McLaws, and, with the main body of the cavalry, will cover the route of the army, bringing up all stragglers that may have been left behind.

IX. The commands of Generals Jackson, McLaws, and Walker, after accomplishing the objects for which they have been detached, will join the main body of the army at Boonsborough or Hagerstown.

X. Each regiment on the march will habitually carry its axes in the regimental ordnance wagons, for use of the men at their encampments, to procure wood, &c.

By command of General R. E. Lee:

R. H. CHILTON,

Assistant Adjutant-General.

*OR, pt. II, 603. Note that the copies sent to D.H. Hill, the "Lost Order," omitted paragraphs I and II above.

______________________Blackford, William W. War Years with Jeb Stuart. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1945; Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

Brown, J. Willard. The Signal Corps in the War of the Rebellion. Boston: U.S. Signal Corps Association, 1896. Reprint, Baltimore: Butternut and Blue, 1996.

Carman, Ezra A. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Ezra A. Carman's Definitive Study of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam, ed. Joseph Pierro. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Croffut, W. A. and Morris, John M. The Military and Civil History of Connecticut during the War of 1861-65. New York: Ledyard Bill, 1868. Reprint, Newport, VT: Tony O'Connor Vt. Civil War Enterprises, n.d.

Davis, Burke. Jeb Stuart: The Last Cavalier. New York: Rinehart, 1957; New York: Wings Books, 1992.

Dowdy, Clifford, and Manarin, Louis H. The Wartime Papers of R.E. Lee. New York: Bramhall House, 1961.

Fishel, Edwin C. The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996.

Freeman, Douglas Southall. Lee: An Abridgement in One Volume by Richard Harwell of the Four Volume R.E. Lee. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1961.

Harsh, Joseph L. Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee and Confederate Strategy and the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1999.

________ Confederate Tide Rising: Robert E. Lee and the Making of Southern Strategy, 1861-1862. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1998.

________ Sounding the Shallows: A Confederate Companion for the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 2000.

Hartwig, D. Scott. "Who Would Not Be a Soldier: The Volunteers of '62 in the Maryland Campaign." In The Antietam Campaign, ed. Gary W. Gallagher. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Johnson, Bradley T. "Reunion of Virginia Division A.N.V. Association." Southern Historical Society Papers. Richmond: Southern Historical Society, n.d. Reprint, Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint Co., 1977.

Jones, Wilbur D. "Who Lost the Lost Order?" Civil War Regiments: A Journal of the American Civil War 5:3, (1997).

Lee, Robert E. Lee the Soldier, ed. Gary W. Gallagher. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

Longacre, Edward G. Lee's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002.

Murfin, James V. The Gleam of Bayonets: The Battle of Antietam and the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965.

Rafuse, Ethan S. McClellan's War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2005.

Relyea, William H. 16th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, ed.-in-chief John Michael Priest. Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 2002.

Russell, Steve, Lieutenant Colonel, USA. "The 27th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment" from http://www.geocities.com/Pentagon/Barracks/3627/facts.html, accessed 20 September 2007.

Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983.

Thomas, Emory M. Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart. New York: Random House, 1988.

Tidwell, William A., Hall, James O., and Gaddy, David Winfred. Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1988.

Time-Life Books. The Civil War: Spies, Scouts and Raiders, Irregular Operations. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985.

U.S. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 128 vols. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1880-1901. Reprint, Harrisburg: Broadfoot Publishing Company, 1985.

1 Murfin, James V., The Gleam Of Bayonets: The Battle Of Antietam And Robert E. Lee's Maryland Campaign, September, 1862, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965, pg. 133 [AotW citation 697]

2 US War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (OR), 128 vols., Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1880-1901, Ser. 1, Vol. 19, Pt. 2, g. 590 [AotW citation 698]

3 Ibid., pg. 594. [AotW citation 699]

4 Carman, Ezra A, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Ezra A. Carman's Definitive Study of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam, ed. Joseph Pierro, (New York: Routledge, 2008), 13, 24-26, 28, 34. See also the address of Bradley T. Johnson in "Reunion of Virginia Division A.N.V. Association" from Southern Historical Society Papers, (Richmond: Southern Historical Society, n.d., reprint Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint Co., 1977, Vol. XII, 506. [AotW citation 700]

5 OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 19, Pt. 2, pg. 600; Carman, pg. 34. [AotW citation 701]

6 Harsh, Joseph L., Taken at the Flood, Kent (Oh): Kent State University Press, 1999, pg. 14 [AotW citation 702]

7 Ibid., 21, 37-39; Lee had one third of all Conf regiments, 206, which might have helped contribute to Federal overestimates; they averaged 360 men per regiment giving some 75,000 total. Importantly, these soldiers were mostly experienced unlike many Union soldiers. But see Fishel, 267, showing 181 regiments and 10 irregular units totaling some 97,445 men, found in OR, pt. 1, 67. For mid-campaign Confederate strength, see Harsh, 170-171, estimating 70,000-75,000. See also Carman, Appendix J, for a thorough discussion of Union and Confederate strength. It shows Union "present for duty" on 17 September as 87,164, with 55,956 engaged; Confederate engaged aggregate 37,351. Confederate present for duty estimates range from less than 30,000 to 41,500. [AotW citation 703]

8 Harsh, 77. The best sources for Lee's and Jefferson Davis's strategic thinking for the Maryland Campaign is found in two books both by Joseph L Harsh, Confederate Tide Rising: Robert E. Lee and the Making of Southern Strategy, 1861 ñ 1862, (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1998); and, Taken at the Flood. Arguably the most thorough books written on Lee's strategy and tactics from the Peninsular Campaign through the Maryland Campaign, Professor Harsh dissects every document available to and written by Lee to give a comprehensive description and analysis of Lee's and his army's actions. These indispensable books are enhanced by his third book, Sounding the Shallows: A Confederate Companion for the Maryland Campaign of 1862, (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 2000), which provides additional discussion for controversial points in the other two books and also gives details of more mundane items such as weather information available for the days of the campaign. Harsh is less critical than most about McClellan's actions during the Maryland Campaign but arguably harsher on Lee and some of his lieutenants than most historians. Unless otherwise stated, all references below to "Harsh" pertain to Taken at the Flood. See also Carman, 42. [AotW citation 704]

9 Carman, pg. 60. [AotW citation 705]

10 Carman, 70-72. [AotW citation 706]

11 Hartwig estimates that about twenty percent of McClellan's strength was composed of raw recruits with little or no training and therefore "significantly affected its mobility and combat effectivenessÖ.McClellan's new regiments lacked discipline; most of their company and many of their field officers were unfamiliar or uncomfortable with their duties and responsibilitiesÖ [and] exhibited incredible ignorance of elementary commands and duties"

Hartwig, D. Scott, and Gary W. Gallagher, editor, Would Not Be a Soldier: The Volunteers of '62 in the Maryland Campaign, The Antietam Campaign, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999, pg. 147 [AotW citation 707]

12 Carman, 84. [AotW citation 708]

13 Harsh, 119, 121; Edwin C. Fishel, The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996), 215; Johnson, 508, 511; McClellan also mentioned the possibility of Lee moving on Washington along the north side of the Potomac, Carman, 84. [AotW citation 709]

14 W. A. Croffut and John M. Morris, The Military and Civil History of Connecticut during the War of 1861-65, (New York: Ledyard Bill, 1868; reprint, Newport, VT: Tony O'Connor Vt. Civil War Enterprises, n.d. ), 299 (page citations are to the reprint edition). See also William H. Relyea, 16th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, ed. in chief John Michael Priest, (Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 2002), 13, 16. Carman, 85. OR, pt. 2, 226-7. [AotW citation 710]

15 Hartwig, 167. [AotW citation 711]

16 Harsh, 229-30. [AotW citation 712]

17 Fishel, 6. [AotW citation 713]

18 Tidwell, William A., and James O. Hall, and David Winfred Gaddy, Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1988, pp. 106-8 [AotW citation 714]

19 Fishel, 571. See also Tidwell, 112. [AotW citation 715]

20 Ibid., 238. [AotW citation 716]

21 Longacre, William G., Lee's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia, Mechanicsburg (Pa): Stackpole Books, 2002, pg. 289 [AotW citation 717]

22 Mosby's Memoirs (page numbers from the J. S. Sanders 1995 edition). Also, Wistar, Isaac J., Autobiography of Isaac Jones Wistar 1827-1905: Half a Century in War and Peace, (Philadelphia: The Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology, 1937), 407-409. Wistar notes that Mosby was not yet a commissioned officer but Mosby states that he was a first lieutenant as of February 1862 even though his status was in limbo for a year after his regiment was reorganized in April 1862, Mosby, 109. Note that Lee called him a "Private" when he commended his service in General Orders 74 dated 23 June 1862, Dowdy, Clifford, and Manarin, Louis H., The Wartime Papers of R.E. Lee, (New York: Bramhall House, 1961), 198.

Mosby, John Singleton, and Charles W. Russell, editor, The Memoirs of Colonel John S. Mosby, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1917, pp. 144-145 [AotW citation 737]

23 Dowdy, 252. [AotW citation 738]

24 Bakeless, John, Spies of the Confederacy, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1970, pp. 78-80 [AotW citation 739]

25 Ibid., 77. [AotW citation 740]

26 Carman, 43-44. [AotW citation 741]

27 Harsh, 111-113. [AotW citation 742]

28 Burke Davis, Jeb Stuart, The Last Cavalier, (New York: Rinehart, 1957; New York: Wings Books, 1992), 211. Emory M. Thomas, Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart, (New York: Random House, 1988), 128. [AotW citation 743]

29 Davis, 195. [AotW citation 744]

30 Priest, 45. [AotW citation 745]

31 Ibid., 50. [AotW citation 746]

32 Blackford, William W., Lt. Col CSA, War Years with Jeb Stuart, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1945, pg. 140 [AotW citation 747]

33 Dowdy, 194. [AotW citation 748]

34 Tidwell, 87-96. The Secret Line was one of the best sources of northern newspapers and periodicals which Lee lost upon his move into Maryland. [AotW citation 749]

35 Dowdy, 241. [AotW citation 750]

36 Harsh, 9, 79. Early in the campaign, Lee in a 4 September dispatch to President Jefferson Davis said that he had read in the Baltimore Sun of the evacuation of Winchester. See also Harsh, 522, n. 84. [AotW citation 751]

37 Fishel, 212; OR, part 2, 201; Carman, 83. [AotW citation 752]

38 Harsh, 108. [AotW citation 753]

39 Ibid., 77, 81-83. [AotW citation 754]

40 Ibid., 205. [AotW citation 755]

41 Carman shows Pleasonton's cavalry division with 4,320 troopers and Stuart's estimated at 4,500; both numbers include horse artillery. [AotW citation 756]

42 OR, pt. 1, 816. [AotW citation 757]

43 Harsh, 198. [AotW citation 758]

44 Ibid., 205. [AotW citation 759]

45 OR, pt. II, 200-201. [AotW citation 760]

46 Harsh, 173. [AotW citation 761]

47 Gallagher, Gary W., Editor, Lee the Soldier, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996, pg. 25 [AotW citation 762]

48 Harsh, 119. [AotW citation 763]

49 Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee: An Abridgement in One Volume by Richard Harwell of the Four-Volume R.E. Lee, (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1961), 243; Harsh, Sounding the Shallows, 176, 193. [AotW citation 764]

50 Harsh, 476. [AotW citation 765]

51 Fishel, 213. See also Carman, 88, who says that no scout could penetrate Stuart's screen. [AotW citation 766]

52 Fishel, 215, 322; Sears, 103. One of Halleck's scouts, W. J. Gaines, reported to Halleck on 14 September that Longstreet and Hill were at Leesburg when they were, in fact, well to the north, OR, pt. 2, 292, thus the quality of reports obtained from Halleck's scouts contributed to the confusion in Washington. [AotW citation 767]

53 Fishel, 215. A guide was also used in the Union cavalry breakout from Harper's Ferry, Carman, 135. Confederates also used guides as McLaws states in a report, Carman, 142. [AotW citation 768]

54 A quotation from Major T. J. Ratchford's manuscript; Ratchford was Hill's chief of staff.

Bridges, Hal, Lee's Maverick General: Daniel Harvey Hill, Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 1991, pg. 98 [AotW citation 769]

55 Harsh, 241. [AotW citation 770]

56 Fishel, 238. [AotW citation 771]

57 OR, vol. 12, pt. III, 710. [AotW citation 772]

58 OR, pt. II, 233. Harsh shows that the Confederate fit for duty on 2 September 1862 was 75,528, Sounding the Shallows, 139; while Lee's strength for those actually fighting on 17 September at Antietam was 37,351 with 10,316 becoming casualties; 201-202. McClellan estimated that Lee had 97,445 present and fit for duty on 17 September, while he had 87,164, OR, pt. 1, 67. McClellan's total casualties from 3-20 September were 15,220 OR, pt. 1, 36. [AotW citation 773]

59 Fishel, 217; OR, pt. II, 254. [AotW citation 774]

60 OR, pt. I, 248. [AotW citation 775]

61 Sears, Stephen W., Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983, pg. 103 [AotW citation 776]

62 OR, pt. II, 198. See also Carman, 45, showing infantry attempting to destroy C&O Canal locks and berms and B&O Railroad facilities including presumably any Union telegraph lines in the vicinity. [AotW citation 787]

63 Carman, 103. [AotW citation 777]

64 Pictured here is a photograph of a signalman preparing to tap into wires; a picture of a pocket key is also shown.

Davis, William C., The Civil War: Spies, Scouts and Raider, Irregular Operations, Alexandria (Va): Time-Life Books, 1986, pp. 68-69 [AotW citation 778]

65 Fishel, 218-40, passim. [AotW citation 779]

66 Ibid., 212. [AotW citation 780]

67 Fishel, 211; Carman, 86. [AotW citation 781]

68 Miner is credited with sending the first official notice of the Confederate advance actually received in Washington. Union signal officers were also initially sent to Maryland Heights, Point of Rocks, Poolesville, and Seneca. Poolesville was abandoned as was Sugarloaf; Seneca was temporarily abandoned as the Confederates advanced. But see Johnson, 518, concerning lack of use of potential signals from Union forces on Catoctin Mountain to Maryland Heights. He conjectures that had Burnside made use of signals on 13 September, Harper's Ferry might have been warned to hold pending relief.

Brown, J. Willard, The Signal Corps, U.S.A. in the War of the Rebellion, Boston: U.S. Veteran Signal Corps Association, 1896, pp. 325-330 [AotW citation 782]

69 OR, pt. II, 238. Carman believes that if Sugarloaf had been carried on 10 September as it should have except for the dilatory actions of Pleasonton, Couch and Franklin, Lee's movements out of Frederick might have been seen, 87. [AotW citation 783]

70 OR, ser. I, pt. I, vol. 51, 807; Brown 327. [AotW citation 784]

71 OR, pt. II, 254, 271; OR, pt. I, 127; Brown, 326. The telegraph line from Point of Rocks to Washington was apparently operating as early as 12 September. [AotW citation 785]

72 OR, pt. II, 258; Harsh 189. [AotW citation 786]

73 Brown, 325. [AotW citation 788]

74 Brown, 331. [AotW citation 789]

75 Carman, 82-3. Here, Union cavalry scouting efforts run up against Hampton's trooper screen. Later, Farnsworth succeeded in pushing Munford back, however, skirmishing later on 9 September by Hampton's troopers pushed Union cavalry back. [AotW citation 790]

76 Carman, 96. Halleck apparently also employed his own scouts adding to McClellan's plethora of sometimes conflicting information. [AotW citation 791]

77 Harsh, Sounding the Shallows, 160-3. He says that there were at least seven and possibly eleven copies. [AotW citation 792]

78 In this well-researched article, Jones argues convincingly that the most likely culprit was Henry Kyd Douglas based on his personality, the opportunities he had, and that he had delivered Jackson's copy of the order earlier to Ratchford.

Jones, Wilbur D., Who Lost the Lost Order? Stonewall Jackson, His Courier, and Special Orders No. 191, Published c. 2002, first accessed 01 June 2006, <http://www.geocities.com/Pentagon/Barracks/3627/loser.html> [AotW citation 793]

79 This regiment was known as the tallest in the army having an average height of 5 feet 9 inches, and having the tallest man in the army, a Capt. David Van Buskirk, who was almost 7 feet tall. See "The 27th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment" from http://www.geocities.com/Pentagon/Barracks/3627/facts.html, accessed 20 September 2007. This site was created by Lt. Col. Steve Russell, Infantry, United States Army. [AotW citation 794]

80 Sears, 112-3. [AotW citation 795]

81 OR, pt. II, 182. [AotW citation 796]

82 OR, pt. 1, 139. [AotW citation 797]

83 Harsh, 315; Sears 89. [AotW citation 798]

84 Harsh, 241, 252. [AotW citation 799]

85 Lee (Gallagher), 26; Fishel, 223. But see Harsh, Sounding the Shallows, in which he concludes that "it seems likely that Lee did knowóor at least assumedÖearly on the morning of September 14 that a copy of S.O. 191 had fallen into McClellan's hands," 175. [AotW citation 800]

86 Lee (Gallagher), 26 [AotW citation 801]

87 Fishel, 223. [AotW citation 802]

88 Ibid., 240 [AotW citation 803]

89 Ibid., 226. [AotW citation 804]

90 Harsh, 238-41. [AotW citation 805]

91 Ibid., 299. [AotW citation 806]

92 Sears in Landscape Turned Red is one among many who find McClellan seriously lacking in his efforts to bring Lee to an annihilating battle after discovering the Lost Order. Harsh is the leader among those historians who believe that given what McClellan knew or believed about Lee's dispositions and strength, he did well, or as well as a Union general commanding the Army of the Potomac could do. He is joined by others such as Ethan S. Rafuse in McClellan's War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2005). Rafuse's sympathetic perspective argues that given McClellan's political views and his philosophy, he did well accomplishing his mission during the campaign. [AotW citation 807]