Open main menu

Open main menu

Open main menu

Open main menu

Author and historian Timothy Reese, a noted authority on the Battle of Crampton's Gap, has consented to have AotW present here the principal content of his reference website, formerly hosted on Earthlink, now withdrawn from service. This page from that site discusses his view of Crampton's as a battle separate from the action at Turner's and Fox's Gaps.

See also his main Crampton's Gap page.

Concerning whether one or two battles were fought on South Mountain, September 14, 1862, opposing army commanders leave no doubt that twin battles took place per Official Records 19/1, p. 140:

[Lee to Davis, Sept. 16, 1862] Longstreet advanced rapidly to his [Hill's] support, and immediately placed his troops in position. By this time Hill's right had been forced back, the gallant Garland having fallen in rallying his brigade. Under General Longstreet's directions, our right was soon restored, and firmly resisted the attacks of the enemy to the last. His superior numbers enabled him to extend beyond both of our flanks, and his right was able to reach the summit of the mountain to our left, and press us heavily in that direction. The battle raged until after night; the enemy's efforts to force a passage were resisted, but we had been unable to repulse him.

Lee refers to "our right" and "our left" clearly indicating joint tactical operations to defend his left at Turner's Gap and his right at Fox's Gap involving brigades of both Hill's and Longstreet's commands. Lee did not consider the two separately, rather mutually dependent in tactical defense. Had all actions on South Mountain been part of a larger whole Lee would have defined his—"our"—right at Crampton's Gap. Lee goes on to evaluate a concurrent action far removed from his immediate orchestration and influence:

Learning later in the evening that Crampton's Gap (on the direct road from Fredericktown to Sharpsburg) had been forced, and McLaws' rear thus threatened, and believing from a report from General Jackson that Harper's Ferry would fall next morning, I determined to withdraw Longstreet and D. H. Hill from their positions and retire to the vicinity of Sharpsburg, where the army could be more easily united. Before abandoning the position, indications led me to believe that the enemy was withdrawing, but learning from a prisoner that Sumner's corps (which had not been engaged) was being put in position to relieve their wearied troops, while the most of ours were exhausted by a fatiguing march and a hard conflict, and I feared would be unable to renew the fight successfully in the morning, confirmed me in my determination. Accordingly, the troops were withdrawn, preceded by the trains, without molestation by the enemy, and about daybreak took position in front of this place [Sharpsburg].

Though fighting his opponent to a standstill in the battle of South Mountain (Turner's and Fox's gaps), Lee underscores a separate action six miles to the south, one over which he had no command control, one which abruptly opened Crampton's Gap to his vulnerable strategic midsection. Lee hesitated in belief "the enemy was withdrawing," but nevertheless resigned himself to evacuation, fearing "[I] would be unable to renew the fight successfully in the morning."

By his own words Lee fought two battles on South Mountain.

His adversary, Gen. George B. McClellan, is also quite specific on this point. Armed with the famed "Lost Order," McClellan utilized Gen. William B. Franklin's Sixth Corps—detached at distance from McClellan's main army since leaving Washington—to drive between Lee's forces at Boonsboro and Harpers Ferry via Crampton's Gap to "cut the enemy in two and beat him in detail." This strategic initiative was launched wholly irrespective of McClellan's tactical assault on Turner's Gap per Official Records 19/1, p. 45:

[McClellan to Franklin, 6:20 P.M., Sept. 13, 1862] If this pass [Crampton's] is not occupied by the enemy in force, seize it as soon as practicable, and debouch upon Rohrersville, in order to cut off the retreat of or destroy McLaws' command. If you find this pass held by the enemy in large force, make all your dispositions for the attack and commence it about half an hour after you hear severe firing at the pass on the Hagerstown pike, where the main body will attack.

McClellan clearly defines a separate objective and conflict for his "main body" at distance from Franklin's wholly distinct objective and ground. By his own words McClellan fought two battles on South Mountain.

We must be willing to accept the unambiguous testimony of Lee and McClellan on matters of strategic importance which they themselves devised and orchestrated. We cannot now know better than they did.

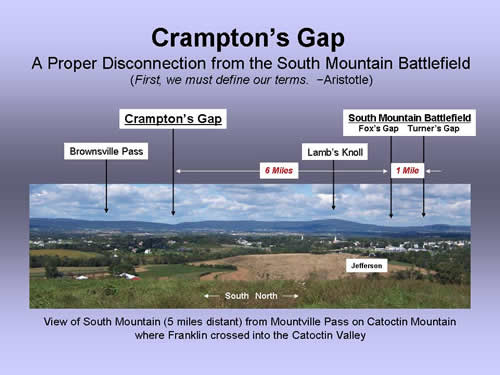

South Mountain from Mountville Pass on Catoctin Mountain![]()

Only in recent times has Crampton's Gap been absorbed into the South Mountain battlefield both strategically and tactically. One can easily fall into the habit of grouping them together in broad-brush campaign summary making strategic complexities simpler to grasp, but far easier to misconstrue.

In the thoroughly documented strategy, words, and actions of both Union and Confederate army commanders, Crampton's Gap clearly stands apart. Grouping these two battlefields as one, disconnected by six miles, confuses and misdirects specialists and novices alike. This same misimpression would persist if, for example, the Salem Church battleground were labeled as part of the Chancellorsville battlefield, oddly enough separated by like distance, also defining Sixth Corps operations. South Mountain—that is, Turner's and Fox's gaps—is a clear instance of joint, primary tactical operations. Crampton's Gap was without question a fundamentally strategic operation, exclusively triggered by the Lost Order. Hybridizing the two does both a grave disservice.

It is sometimes implied that McClellan's response to S.O. 191 must be measured exclusively by army movements on the National Turnpike. True, his right wing, Burnside's First and Ninth Corps, and center, Sumner's Second and Twelfth Corps, were piling into Frederick and beyond into the Catoctin Valley by the 13th, this the bulk of his forces. However, this utterly disregards his salient response to the Lost Order, namely injection of his left wing, Franklin's Sixth Corps, through Crampton's Gap to prevent Longstreet and Jackson reuniting. This would free McClellan to descend in strength on an isolated Longstreet—including Lee in person—west of South Mountain with dramatic numerical superiority. Had it worked, there would have been no Antietam, maybe a Boonsboro or some other westerly locale alternately famed to posterity.

To employ a boxing metaphor, McClellan's strong right arm was slated to pound Lee's rear guard under D.H. Hill at South Mountain, first at Fox's Gap, then at Turner's, while Franklin's Sixth Corps would administer a left hook through Crampton's Gap six miles to the south—a one-two punch. This latter stroke would accomplish McClellan's mandate to "cut the enemy in two and beat him in detail", facilitating "the decisive results I propose to gain" by his attacking an outnumbered and unaided Longstreet. Neither punch had the desired intensity or effect. Burnside failed to shove Hill off the mountain onto Boonsboro. Though wholly victorious, Franklin failed to pursue his westward progress to interpose between Longstreet and Jackson, with or without additional troops absorbed from the Harpers Ferry garrison.

All campaign documents underscore disconnection. In their reports both Lee and McClellan recorded these two distinctly in both strategic and tactical senses. The entire range of corps, division and brigade subordinates recorded likewise, as well army support branches. Strengths and casualties were also reported separately. Generated by unblinking army bureaucracies, this documentation later served as groundwork for all subsequent analyses compiled by veteran-historians, statisticians and memorialists.

However misunderstood may be the four days bridging the Lost Order to Antietam, the battle of South Mountain must be classified as a secondary strategic response to the Lost Order. This is not to infer that it emerges inconsequential, quite the contrary. Fortunately for McClellan, the main body of his army was already well positioned on the National Turnpike, albeit in grossly extended order, when the Lost Order came to light. Before nightfall his lead element, the Ninth Corps, had reached Middletown from whence it would reconnoiter Fox's Gap next morning.

Under Gen. Ambrose Burnside's direction South Mountain evolved as a joint extended flanking maneuver spanning two miles of mountain crest for control of the National Turnpike through Turner's Gap. One mile below it, Fox's Gap was to be seized from which point Ninth Corps troops could then drive northward along the summit to pressure Hill out of Turner's Gap. Hooker's First Corps made a remarkable twelve-mile forced march, from the banks of the Monocacy through Frederick and Middletown on the National Turnpike, to the foot of the mountain via the Old Hagerstown Road, going straight into combat north of Turner's. Burnside's attempt at coordinated gap assaults however delayed deployment, allowing D.H. Hill barely enough time to race his Confederate brigades, reinforced by those of Longstreet, to each emerging crisis point. The result was repeated savage head-on collisions, first at Fox's then at Turner's Gap, in what can only be described as irresistible forces pitted against immovable objects. On the key National Pike itself John Gibbon's legendary "Black Hat Brigade" met its match in the Georgia brigade of Alfred Colquitt, the "Rock of South Mountain." Despite heroic obstinacy, Hill's outnumbered "objects" were nevertheless marginally moved aside by day's harrowing end. A narrow Confederate tactical victory was just barely achieved vouching safe Lee's artillery reserve and wagon trains.

That night exhausted Confederates still resolutely clung to ground from which their fire could be brought to bear on the Old Sharpsburg Road next morning, further contesting passage through Fox's Gap. At Turner's Gap the situation seemed hopeless when Union troops seized and held the summit just north of the gap. Lee had virtually nothing left with which to hold the crest line next day. Weighing his dismal options with Longstreet and Hill that night, he then learned of the last straw at Crampton's Gap.

Franklin had had a much easier time of it, though he felt just the opposite. Here Crampton's Gap quickly fell as McClellan had anticipated, clearing the way for permanent division of Lee's forces. Before this Lee might have pulled back behind Boonsboro, seeking ground to which he might cling until Jackson came up from Harpers Ferry after its anticipated surrender. But time had run out. Lee would march, not Jackson.

In ranking the two concurrent battles on South Mountain, varying criteria must be taken into account. Through size alone, precedence must be assigned in descending order of gaps north to south, Turner's, Fox's, and Crampton's. Measured in Federal tactical success, they would be prioritized Crampton's, Turner's, and then Fox's. Strategically speaking however, Crampton's Gap again surpasses both northern gaps individually and collectively by merit of its impact on Lee's rapidly dwindling options.

South Mountain froze the campaign initiative. Crampton's Gap wrenched it from Lee's grasp and conclusively closed his expedition into Maryland. Without Crampton's Gap there would have been no Antietam.

Therefore Crampton's Gap and South Mountain were, and remain, two wholly separate though synchronous engagements, fought independently by autonomous wings of both armies for wholly distinct campaign objectives.

Gen. George S. Patton later uttered a pithy analogy applicable to this mountaintop predicament. While Burnside held Lee "by the nose" in the battle for South Mountain, Franklin was sent forth to "kick him in the ass" at Crampton's Gap while Lee was desperately distracted—or more accurately and delicately put, in his vacant breadbasket. Duality of purpose is inescapable.(excerpt from High-Water Mark: The 1862 Maryland Campaign in Strategic Perspective, now available, see Books page.)

-- Timothy Reese, Burkittsville, Maryland

AotW Member

© 2000, Tim Reese

published online previously as part of the website at http://home.earthlink.net/~tjreesecg/index.html