Open main menu

Open main menu

Open main menu

Open main menu

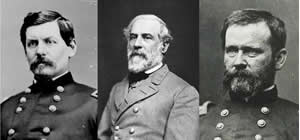

Generals McClellan, Lee, and Franklin

Author and historian Timothy Reese, a noted authority on the Battle of Crampton's Gap, has consented to have AotW present here the principal content of his reference website, formerly hosted on Earthlink, now withdrawn from service. This page from that site quotes some direct sources on the battle.

See also his main Crampton's Gap page.

A battle is only truly great or small according to its results. —Mark Twain

The battle for Crampton's Gap was the direct strategic link between the famed "Lost Order" and the climactic battle of Antietam. Some still find this difficult to accept when conventional literary wisdom says otherwise. The following quotations taken from primary sources provide fundamental evidence recorded by army commanders, boldface added for emphasis.

I have now full information as to movements and intentions of the enemy....My general idea [at Crampton's Gap] is to cut the enemy in two and beat him in detail. I ask of you, at this important moment, all your intellect and the utmost activity that a general can exercise....You will readily perceive that no slight advantage should for a moment interfere with the decisive results I propose to gain.

—Gen. George B. McClellan to Gen. William B. Franklin, 6:20 P.M., September 13, 1862 (U.S. War Dept., War of the Rebellion...Official Records, 19/1:45-46, 51/1:826-827)

Learning later in the evening that Crampton's Gap (on the direct road from Fredericktown to Sharpsburg) had been forced, and McLaws' rear thus threatened, and believing from a report from General Jackson that Harper's Ferry would fall next morning, I determined to withdraw Longstreet and D. H. Hill from their positions and retire to the vicinity of Sharpsburg, where the army could be more easily united.

—Gen. Robert E. Lee to President Jefferson Davis, September 16, 1862 (U.S. War Dept., War of the Rebellion...Official Records, 19/1:140)

Information was also received that another large body of Federal troops had during the afternoon forced their way through Crampton's Gap, only 5 miles in rear of McLaws. Under these circumstances, it was determined to retire to Sharpsburg, where we would be upon the flank and rear of the enemy should he move against McLaws, and where we could more readily unite with the rest of the army.

—Gen. Robert E. Lee to Confederate Adj. Gen. Off., August 19, 1863 (U.S. War Dept., War of the Rebellion...Official Records, 19/1:147)

This night [September 14-15] Lee found out that Cobb had been pressed back from Crampton's Gap, and this made it necessary to retire from Boonsboro [Turner's] Gap, which was done next morning and position at Sharpsburg taken.

—As told to William Allen by Robert E. Lee at Washington College, Lexington, Va., February 15, 1868 Douglas S. Freeman, Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command (1942-44) vol. 2: Appendix, p. 721. A verbatim transcript of the William Allen memorandum more recently appeared in Gary W. Gallagher, Lee the Soldier (1996) pp. 7-19.

...Crampton's Gap, where McClellan should have gone in person, as that position was the key point of the whole situation.

—Edward Porter Alexander (Lee's Chief of Ordnance), Military Memoirs of a Confederate (1907) p. 23.

If Reese's book fulfills the promise of his unannotated article ["Howell Cobb's Brigade," Blue & Gray Magazine, Winter 1998 issue], a major reevaluation of this battle will be required.

—Joseph L. Harsh, Taken at the Flood (1999), p. 549, note 77.

In the aftermath neither Lee nor McClellan found cause to dwell upon Crampton's Gap in concealing deep mutual disappointment, belying the essential truth that this mountain top shoving match had become, in microcosm, the pivotal battle of the pivotal campaign of America's most pivotal war.

—Timothy J. Reese, Sealed With Their Lives: The Battle for Crampton's Gap (1998)

Francis W. Palfrey, The Antietam and Fredericksburg (1882), pp. 29-31.

It is proper to dwell upon this letter of McClellan's [6:20 P.M., Sept. 13], because it seems to be the first order that he issued after he came into possession of Lee's lost order [sic, Pleasonton, 3 P.M.], and it seems to be indisputable that in issuing it he made a mistake, which made his Maryland campaign a moderate success, bought at a great price, instead of a cheap and overwhelming victory. His "general idea" was excellent, but time was of the essence of the enterprise, and he let time go by, and so failed to relieve Miles, and failed to interpose his masses between the wings of Lee's separated army. "Move at daybreak in the morning." Let us see what this means. Franklin was at Buckeystown. The orders were issued from "Camp near Frederick," at 6.20 p.m. Buckeystown is about twelve miles by road from the top of Crampton's Gap. Franklin's troops, like all the troops of a force marching to meet and fight an invading army, were, or should have been, in condition to move at a moment's notice. The weather on the 13th was extremely fine, and the roads in good condition. There was no reason why Franklin's corps should not have moved that night, instead of at daybreak the next morning. There was every reason for believing that there were no Confederate troops to interfere with him in his march to the Gap, for McClellan knew that they were all fully employed elsewhere, and, if there were, the advance guard would give him timely notice of it, and if he stopped then he would be just so much nearer his goal. We know now that if he had marched no farther than to the foot of the range that night, a distance which he ought to have accomplished by midnight, he could have passed through it the next morning substantially un≠opposed, and that advantage gained, the Federal army ought to have relieved Harper's Ferry or fatally separated the wings of Lee's army, or both. And what we know now, McClellan had strong reasons for believing then, and strong belief is more than sufficient reason for action, especially where, as in this case, he could not lose and might win by speed, and gained nothing and might lose almost everything by delay. He was playing for a great stake, and fortune had given him a wonderfully good chance of winning, and he should have used every card to the very utmost, and left nothing to chance that he could compass by skill and energy. But there are some soldiers who are much more ingenious in finding reasons for not doing the very best thing in the very best way, than they are vigorous and irresistible in clearing away the obstacles to doing the very best thing in the very best way.

As McClellan respected the night's sleep of Franklin and his men, so did he that of the rest of his army. No portion of it was ordered to move that night, with the possible exception of Couch, who was ordered to join Franklin "as rapidly as possible," and no portion of it other than Franklin's was ordered to move so early as daybreak the next morning. The earliest hour for marching that was prescribed to any other command was "daylight," on the 14th, at which hour Hooker was to set out from the Monocacy and go to Middletown.