Open main menu

Open main menu

Open main menu

Open main menu

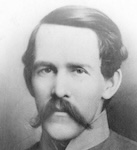

R.E. Rodes

(1829 - 1864)

Home State: Virginia

Education: Virginia Military Institute (VMI), Class of 1848;Class Rank: 10/24

Command Billet: Brigade Commander

Branch of Service: Infantry

Unit: Rodes' Brigade

see his Battle Report

Before Sharpsburg

Born in Lynchburg, Virginia, the third of four children, Robert Emmet Rodes grew up in a comfortable home on Federal Hill there; his father David was a prominent local figure: a Brigadier General in the Virginia militia, dry-goods merchant, and for 20 years Clerk of the Circuit Court. His mother was the former Martha Anne Yancey, whose father Joel was a Major in the War of 1812, afterward overseer of Thomas Jefferson’s plantation Poplar Forest in Bedford County, VA, and substantial landowner in his own right in that county.

Robert received a superior education in private schools in Lynchburg to the age of 16, when he followed his older brother Virginius (Class of 1843) and enrolled as a Cadet in the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in Lexington in July 1845. VMI had opened in November 1839 under the direction of Superintendent Francis Henney Smith, a West-Pointer (1833) who afterward led VMI for 50 years. Colonel Smith looked out for his new charge, as he did all of the Cadets, and would became a lifelong mentor and friend to Rodes.

Although Robert’s class standing was reduced by demerits for “deportment” during the three year program at VMI, he did well in the mathematics and science-based curriculum and finished in July 1848 as Cadet Lieutenant, ranked 10th of the 24 graduates from among the 50 or so who started with him. Along the way he came to believe that rigor and discipline were the foundation of a successful education - and later, of military success.

As he neared graduation, Robert considered an Army career, which Colonel Smith discouraged, telling his father “there are a thousand pursuits which are more agreeable,” nevertheless, Smith sent a strong letter of recommendation which ended:

So highly do I value his service, that I should esteem this Institute fortunate, if we can secure him as an assistant after he graduates.

Rodes did not obtain a commission - the end of the war with Mexico left few available - but did accept Superintendent Smith’s offer to remain at VMI as an instructor in tactics, mathematics, and chemistry. He advanced from Lieutenant to Captain in rank, but, unsatisfied with his low salary, hoped to be advanced to a new position as Major and department chairman as the school expanded in 1850. However, Smith was set on a West Point graduate for the post and it eventually went to Lieutenant Thomas J Jackson, First US Artillery (USMA 1846). His future limited, Rodes resigned from the Institute in February 1850.

Over the next six years he was an engineer on a canal project in Rockbridge County, then on railroads: the Southside at Petersburg, the Texas Atlantic & Pacific, briefly with the North East and South West Alabama (NE&SWA) RR, based in Tuscaloosa, where he met the woman who would later be his wife, and then with the Western North Carolina Railroad as Principal Assistant Engineer; technically challenging work which he completed in the Summer of 1856. His success on that project cemented his reputation as a serious railroad engineer and his exacting leadership style there prefigured that of his later military life.

In October 1856 he rejoined the NE&SWA, bought a small house near Tuscaloosa, went to work laying out the 50 miles of railroad in his charge, and courted 23 year old schoolteacher and book-seller’s daughter Virginia Hortense Woodruff. He and Hortense married the next September. In February 1858 he was promoted to be one of two chief engineers of the railroad and was at the top of his profession. Even so, in 1859 he confided to his old mentor, Colonel Smith at VMI:

I know now and have always known that I would be happier and more useful as a teacher than in my present position.

Happily, the VMI Board of Visitors created a new Chair of Applied Mechanics, making possible Robert Rodes’ fondest wish - to return to VMI. In July 1860, ten years after he had resigned, the Board appointed him to that post to begin in September 1861. Sadly, he would never take the chair.

Following John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in October 1859 Tuscaloosa’s Warrior Guards militia company reformed, Captain Robert E Rodes, commanding. He began training them monthly, while continuing his work for the railroad, and within a year they won a prize as best drilled company in West Alabama. He drilled them daily after Abraham Lincoln was elected President in November 1860. By Christmas nervous investors were pulling out of the NE&SWA, and at Alabama’s secession from the Union in January 1861, Rodes effectively changed his occupation from railroad engineer to military officer.

Alabama Governor Moore sent him and the Guards to hold and defend Fort Morgan in Mobile Bay, and they were in garrison there until relieved by regular Confederate troops in March 1861. In April Captain Rodes took them to Montgomery, where on May 11th they became Company H of the Fifth Alabama Infantry Regiment. In the election of regimental officers, Rodes was chosen Colonel.

His new regiment’s first duty was three weeks at Pensacola, FL where Rodes applied his customary high standards of performance and discipline, then they were ordered north to Virginia, arriving in Richmond on June 9th. A month later, now part of Brig. Gen. Richard Ewell’s Brigade, they were in position near Centreville: advance pickets of the Confederate main line at Manassas. Rodes and his men got their first taste of combat when the lead elements of the advancing Union Army reached them early on July 17th. Ordered to retreat, they fought a delaying, rear guard action for about 13 miles back to the main Confederate position along Bull Run. They were not significantly engaged there in the battle of the 21st. His brigade commander Ewell and overall army commander Beauregard both wrote complementary reports about him; he was gaining a reputation as a steady and capable combat leader.

In October 1861 he was appointed Brigadier General and took command of his own brigade, which by the Peninsula Campaign of the Spring 1862 was in Maj. Gen. Daniel H. Hill’s Division and consisted of the 3rd, 5th, 6th, 12th, and 26th Alabama Regiments. He was wounded in action at Seven Pines on June 1 and briefly hospitalized in Charlottesville, VA but, not fully recovered, returned to command the brigade in battle at Gaines’ Mill on June 27th.

He and his brigade remained with their division in the defenses of Richmond the rest of the summer, but rejoined the Army of Northern Virginia in the field at Chantilly, VA on 2 September and crossed the Potomac River at Cheek’s Ford near Leesburg - the 3rd Alabama Infantry in the lead - in the van of the army as it entered Maryland on September 4, 1862.

On the Campaign

Rodes and his men were at Frederick to September 10th, when, with the rest of the division, they marched at the rear of the Confederate column heading north and west, reaching the village of Boonsboro on the 13th. At mid-day on September 14th they were sent to the summit of South Mountain to reinforce the small force defending Turner’s Gap against the assault of the Union First Army Corps.

Arriving about 1 p.m., Rodes posted his men along the summit to the left (north) of the National Road, but an hour later was ordered to a peak about three-quarters of a mile further north. Rodes did well with the men he had, but by late afternoon his position was penetrated by Union troops of Brig. Gen. George G. Meade’s Division of Pennsylvania Reserves, who overlapped both of his flanks and drove between his regiments. His regimental commanders continued to fight as isolated units for some hours, but were all driven off the summit at nightfall. He later summarized his brigade’s work that day:

We did not drive the enemy back or whip him, but with 1,200 men we held his whole division at bay without assistance during four and a half hours' steady fighting, losing in that time not over half a mile of ground.

His Division commander, D.H. Hill noted:

Rodes handled his little brigade in a most admirable and gallant manner, fighting, for hours, vastly superior odds … Rodes' brigade had immortalized itself.

At 11 p.m. that night Rodes marched his men to Keedysville, and continued on to Sharpsburg at dawn on September 15th. With about 800 men remaining in his brigade, Rodes was in position on the high ground in the center of the Confederate line the rest of that day and all the next, but before 9 a.m. on the 17th was ordered north to assist the brigades of Col. Colquitt and Brig. Gens. Ripley and Garland, then being overwhelmed in David R. Miller’s cornfield and the East Woods. Finding the three in retreat, he formed a defensive line in the sunken road later known as the Bloody Lane, his left, lengthened by survivors of Colquitt’s Brigade, on the Hagerstown Pike, and his right at a bend in the road, where he linked to Brig. Gen. G.B. Anderson’s Brigade.

Soon after, Rodes’ regiments engaged waves of assaulting Union troops of Brig. Gens. French and Richardson’s Divisions. He initially held off the attackers and even made a bayonet charge early in the fight, only to be driven back into the road with heavy loss. After nearly three hours of close combat, Rodes later reported,

[I] met Lieutenant-Colonel Lightfoot, of the Sixth Alabama, looking for me. Upon his telling me that the right wing of his regiment was being subjected to a terrible enfilading fire … I ordered him to … throw his right wing back out of the old road referred to. Instead of executing the order, he moved briskly to the rear of the regiment and gave the command, "Sixth Alabama, about face; forward march." Major Hobson, of the Fifth, seeing this, asked him if the order was intended for the whole brigade; he replied, "Yes," and thereupon the Fifth, and immediately the other troops on their left, retreated.

Although their position had already become untenable, this command error accelerated the disintegration of the Confederate line in the road. At this time Rodes was slightly wounded, struck in the thigh by a piece of artillery shell, but he remained on the field and rallied a few of the survivors of his brigade and other nearby units behind the Hagerstown Pike - a pickup force later led by Brig. Gen. Hill in person in a counterattack into Piper’s orchard.

Rodes and what was left of his command, perhaps 600 men, remained on the battlefield through the next day, and returned to Virginia across the Potomac at Boteler’s Ford on the night of September 18-19, 1862, their campaign over.

The rest of the War

He was present but in reserve at Fredericksburg in December 1862, and when D.H. Hill was transferred to North Carolina in January 1863 Rodes was given his division. He was the first of General R.E. Lee’s division commanders not trained at West Point. They were in the lead of “Stonewall” Jackson's highly successful flank attack on the Federal Eleventh Army Corps at Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, and Rodes was briefly in command of the Confederate Second Corps there after Jackson’s mortal wounding. He was promoted to Major General to date from the battle.

He was not at his best, however, at Gettysburg two months later. On July 1 he drove the Union First Corps back through Gettysburg in a series of disjointed attacks, but on the second day, “[w]hen the time to attack arrived, General Rodes, not having his troops in position, was unprepared to co-operate with General Early, and before he could get in readiness the latter had been obliged to retire for want of the expected support on his right.”

At the Wilderness on May 5, 1864, it was Rodes who stopped the Union Fifth Corps's advance, and at Spotsylvania on May 12th he helped defend and recover the "Mule Shoe" salient. He went to the Shenandoah Valley with Lt. Gen. Jubal Early in June, and led his division on the raid toward Washington, DC, seeing action at Monocacy on July 9th.

Union Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan attacked Early’s greatly outnumbered army in the Valley near Winchester, Virginia on September 19, 1864 in the Battle of Opequon (or Third Winchester), and General Rodes was struck in the back of the head by a piece of an exploding artillery shell as he prepared a counterattack. He fell from his horse and died on the ground moments later. The charge went ahead without him, at least briefly knocking back Sheridan’s assault and giving Early time to gather his troops and retreat safely.

Rodes and his wife Hortense had not had children before the war, probably because she was frequently ill and thought unable to bear the strain of childbirth, but they had their first, son Robert Emmet, Jr., on September 21, 1863, probably in Lynchburg. Hortense bore their daughter Bell Yancey Rodes about four months after Robert’s death, in January 1865 in Tuscaloosa.

References & notes

His service from Warner,1 his Compiled Service Records,2 online from fold3, the ORs,3 and his own after-action report. Personal details from Darrell Collins' Major General Robert E. Rodes of the Army of Northern Virginia: A Biography (2008), family genealogists, and the US Census of 1860; his middle name also seen as Emmett. His gravesite is on Findagrave. His picture from a photograph in the VMI Archives.

He married Virginia Hortense Woodruff (1833-1907) of Tuscaloosa in September 1857 and they had 2 children; Robert, Junior (1863-1925) and Bell (1865-1931).

His brother Virginius Hudson Rodes (1824-1879) was appointed First Lieutenant and aide-de-camp to Robert in July 1864, but his commission expired on the General's death in September.

Birth

03/29/1829; Lynchburg, VA

Death

09/19/1864; Winchester, VA; burial in Presbyterian Cemetery, Lynchburg, VA

1 Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Gray, Lives of the Confederate Commanders, Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1959, p. 263 [AotW citation 31327]

2 US War Department, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers, Record Group No. 109 (War Department Collection of Confederate Records), Washington DC: US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), 1903-1927 [AotW citation 31328]

3 US War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (OR), 128 vols., Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1880-1901, various [AotW citation 31329]